Africans growing more concerned over taxes, fees on digital services

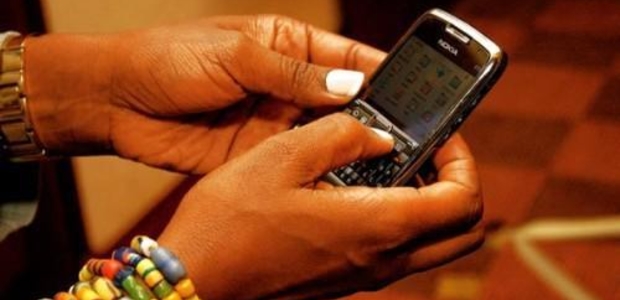

The brisk business Julius Kirya did from his cash transfer kiosk in the Ugandan capital has slowed right down with a new tax on mobile money. Many of his customers have returned to sending banknotes by hand, in some cases via motorbike taxi.

How to tax digital revenues, from fintech to social media, is a puzzle authorities around the world are working on. A solution catching on in Africa – levies on usage – has obvious appeal to indebted governments but a big impact on people like Kirya, who saw the tech revolution as a way out of poverty.

“I had a dream of steadily growing to middle income status,” he said from his tiny cubicle attached to a Kampala petrol station, one of thousands across the country that serve the millions of people without access to bank accounts.

He was making three times the average salary before the tax, was introduced in July. Now his income has slid to half that. “With this tax I have no chance,” he said.

It is not just Kirya and his customers who are losing out.

Mobile communications have revolutionised life in Africa where telecom company reports show calls and texts are giving way to data services like Facebook-owned WhatsApp, Skype, Viber and WeChat owned by China’s Tencent.

The telecom companies say taxes on mobile payments introduced by a string of countries hurt their revenues and threaten much-needed investment in infrastructure.

Levies on social media usage brought in by Uganda and Benin and a proposed tax on internet calls in Zambia have taken the shine off a fast-growing market and have all sparked protests.

Officials say the taxes are needed to preserve state revenues as technologies evolve.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has long pressed African states to improve tax collection, urges caution.

“You want to make sure you don’t introduce taxes that are stifling innovation and curtailing activity in the sector,” Abebe Selassie, the IMF’s top official for Africa, told Reuters this month. “So striking that balance will be important.”

Mobile money transactions are also taking a hit. A spokeswoman for Airtel Uganda, a subsidiary of India Bharti Airtel’s, said the new tax on transfers had led to a significant drop in the volume and value of transactions.

“Any disruption in the Airtel Money operations causes an indirect negative impact on the growth prospects of emerging businesses, stifling economic growth,” said Sumin Namaganda.

Ugandan media have quoted MTN officials saying the tax had cut the company’s mobile transaction volumes in half.

As of March 2017, mobile money services were operating in 39 sub-Saharan African countries with almost 280 million registered accounts, according to mobile communications industry body GSMA.

At least six countries have introduced taxes on the service, prompting GSMA to warn in a report last year that high or unpredictable levies may cost states some of what it said would be $31 billion in investment across Africa, mainly focused on improving data coverage and services.

Some governments appear to be having second thoughts.

Zambia’s proposed levy on internet calls, announced in August, did not make it into the new budget approved last month.

And just three days after Benin introduced its social media tax to widespread public outcry, the government cancelled it, on the grounds it created “instability in the sector’s economy which harms the interest of consumers”.

Uganda’s mobile money tax was introduced as 1 percent levy “on receiving, payments and withdrawals”. Museveni later said the rate was 0.5 percent and applied just to withdrawals. Parliament corrected the law but the president has not enacted the revised text.

While kiosk owners and some of their clients in big cities are struggling on, Kirya said his colleagues operating mobile money kiosks in rural areas had simply shut up shop.

“With this tax everything is getting complicated,” he said.