Tackling Africa’s maternal mortality crisis

In Lesotho’s northern Leribe district, Dimpho Sithole* shares her story of how she almost lost her life after childbirth.

The 20-year-old mother says she was unaware of the many complications that can occur post-delivery.

“I lost a lot of blood after giving birth to my son, but I thought it was normal until I collapsed at home and had to be taken to the hospital. The nurses did not think I would make it,” she said.

“I had heard that heavy bleeding could occur, but I didn’t know what to watch for to be concerned, especially once I was at home.”

Dimpho’s story is one of thousands across sub-Saharan Africa that often end in tragedy. Every day, more than 700 women worldwide die from complications related to pregnancy or childbirth, with over 70 percent of those deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of her pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.

According to medical experts, the vast majority of these deaths are preventable.

“The maternal mortality burden remains high in sub-Saharan Africa due to a convergence of structural, political, and economic challenges that undermine the effectiveness of existing interventions. While maternal mortality rates vary widely across the region, reflecting disparities in healthcare systems and resources, systemic barriers remain pervasive,” said Rajat Khosla, Executive Director of the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH), World Health Organization (WHO).

Despite the challenges, a new study conducted by PMNCH, the world’s largest alliance for women’s and children’s health, shows a roadmap for reversing the scale of the crisis on the continent.

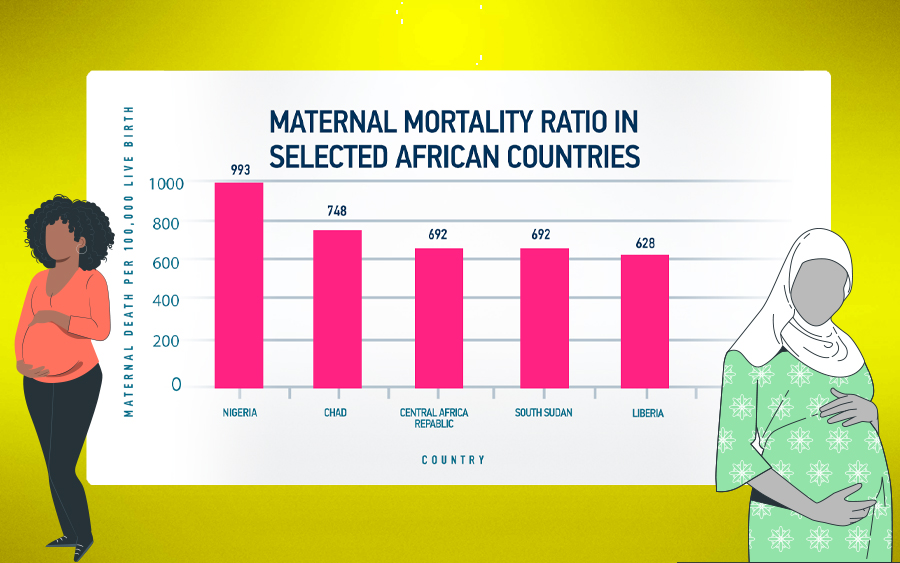

The study reveals significant progress in reducing global maternal mortality, with a 40 percent decrease since 2000. For the first time in history, no country recorded a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) exceeding 1,000 per 100,000 live births.

However, progress remains insufficient to meet global targets. The global maternal mortality ratio decreased at just 1.6 percent annually from 2016 to 2023, far below the 14.8 percent reduction needed to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target of 70 deaths per 100,000 live births.

The gap is particularly evident in sub-Saharan Africa, where the current maternal mortality ratio stands at approximately 454 deaths per 100,000 live births, more than six times higher than the target.

Geography of risk

Khosla explains that the risk a woman faces during pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa varies depending on her location. In 2023, Nigeria led with 75,000 maternal deaths and an MMR of 993 per 100,000 live births, followed by Chad (748), the Central African Republic (692), Liberia (628), and Sierra Leone (443).

“These figures point to persistent gaps in access to quality maternal healthcare, emergency obstetric services, and postnatal care,” he continued.

In contrast, countries like Zambia, Mozambique, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Cabo Verde have achieved MMRs below 200, with some even below 100, through investments in midwifery, health system strengthening, and equitable care distribution.

Leading causes

Khosla highlights three primary killers contributing to maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, and sepsis.

Hemorrhage, which typically occurs after childbirth, remains the leading cause, responsible for approximately 28 percent of all maternal deaths in the region.

“Despite proven, cost-effective interventions like uterotonics and tranexamic acid, we continue to lose mothers to bleeding,” Khosla notes. “This highlights critical gaps in healthcare quality and access, especially in facilities lacking trained personnel, essential medications, and emergency response capabilities.”

Hypertensive disorders rank second among direct causes of maternal death. These conditions, characterized by dangerous spikes in blood pressure during pregnancy, often require timely detection and management with medications.

For teenage mothers, the risks are particularly acute. “Girls aged 15-19 are twice as likely to die during childbirth compared to women aged 20 and above,” Khosla points out. “This reflects not just biological vulnerability but societal failures.”

African-driven solutions

Khosla emphasizes that political will is critical to accelerating progress. Effective governance and targeted health policies have been instrumental in improving maternal health outcomes.

“An interesting example is Sierra Leone,” he notes, “which boldly declared maternal mortality a public health emergency, mobilizing resources and triggering a coordinated multisectoral response.”

Another initiative is the Global Leaders Network (GLN) for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health, chaired by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Launched in 2024, the network unites heads of state from countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania, aiming to reduce maternal mortality by a third by 2030 through advocacy and policy reform.

The continent has also seen a rise in technological innovations that assist mothers and their infants.

One example is m-mama, a Vodafone Foundation and USAID mobile application operating in Kenya, Lesotho, and Tanzania. It connects expectant mothers in rural areas to emergency transport through a dispatcher system.

Others include MomConnect, a South African SMS-based platform providing pregnant women with vital health information and reminders.

In Nigeria, Hello Mama helps reach low-literacy women through a voice-based service that provides maternal health guidance.

Although significant progress has been made in reducing maternal mortality, more needs to be done to ensure better access for women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Through her advocacy in surrounding villages in Lesotho, Dimpho hopes to join the fight to save expectant mothers.

CGTN Africa editor Regina Mulea contributed to this report.