Wires of Hope: Solar fences protecting farms and wildlife in Tsavo

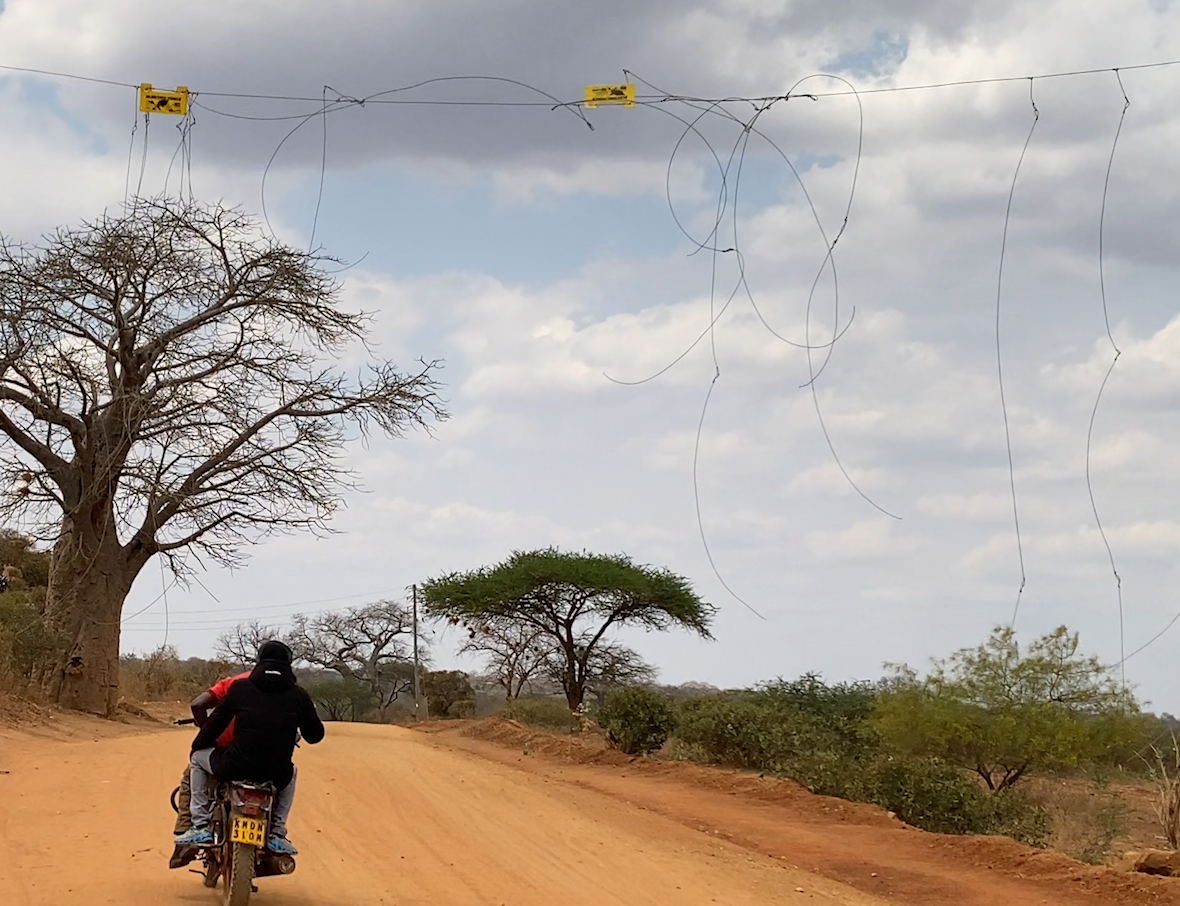

On the farthest edge of Tsavo West National Park, the border between farmland and wilderness is marked not by walls, but by a thin line of wire humming softly with solar power. Beyond it, elephants roam freely. On this side, crops thrive and communities sleep peacefully again.

“I live on the border of the park, right at the farthest end,” says Riziki Mbithi, a resident farmer in Mtito Andei. “From here to the river is about 100 to 200 meters. When we first moved here in 1996, there were all kinds of animals. Buffaloes and baboons were our biggest problem, but later, elephants began destroying everything we planted.”

She remembers sleepless nights as elephants trampled through her banana and pawpaw plantations, knocking down trees and water tanks.

“We were completely at their mercy. Sometimes I’d hear them coming, bringing down trees as they marched,” she recalls. “A lot was destroyed during those violent nights.”

Then came hope in the form of a solar-powered fence.

A Solar Solution to Human-Wildlife Conflict

According to Moffat Peter, Monitoring and Evaluation Officer at Tsavo Trust, the nonprofit behind the initiative, human-elephant conflict had become a major issue along the northern boundary of Tsavo West before 2022.

“One of the key mitigation measures we implemented was the elephant exclusion fence — a 33-kilometer, solar-powered barrier designed to prevent elephants from entering farmlands,” he explains. “Before we constructed the fence, crop raids were so frequent that farming households could hardly harvest anything. There were even cases of injuries and deaths.”

The project was a collaborative effort between Tsavo Trust, Kenya Wildlife Service, and the Makueni County Government. Since its installation, cases of human-elephant conflict have decreased by more than 80 percent, directly benefiting over 8,000 people through improved food security and restored livelihoods.

How It Works

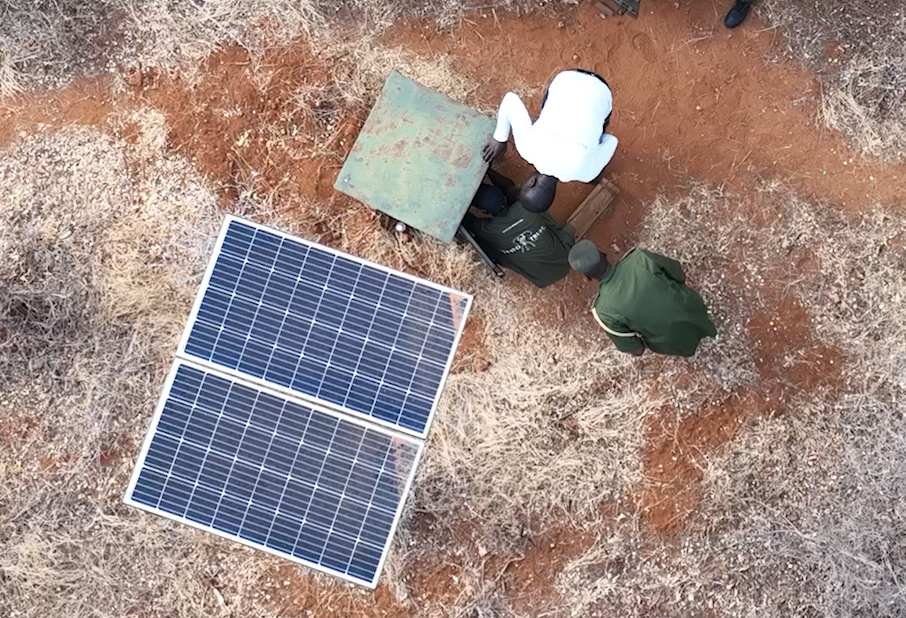

The fence runs 33 kilometers long and is powered entirely by solar energy — a necessity in an area not connected to the national electricity grid.

“We have six solar units, with two covering every 11 kilometers,” Moffat explains. “They charge batteries that power the energizers, ensuring the fence remains active even at night.”

Each of the three fence technicians, recruited from the Kamungi Conservancy community, is responsible for maintaining an 11-kilometer stretch, clearing vegetation, checking voltage, and making repairs.

“Since the fence was installed four years ago, we’ve maintained stable voltage with minimal challenges. Once you invest in quality solar systems, they last long and eliminate recurring costs,” he adds.

Importantly, the voltage is strong enough to deter elephants but harmless to both wildlife and humans. “We’ve never had any incidents of injury,” Moffat says. “The goal is to keep elephants away, not hurt them.”

Community Conservation in Action

Tsavo Trust has worked with communities on the northern boundary of Tsavo West for over 12 years, championing the creation of Kamungi Conservancy, a community-led model that now inspires others across Kenya.

“The key to sustainable conservation is involving local communities from start to finish,” Moffat emphasizes. “We co-fund projects so that communities contribute what they can, building ownership and pride in the process.”

Over the years, the organization’s impact has grown beyond wildlife protection to include water projects, education support, and food security programs. More than 60 local residents have been employed, 159 households now use home solar systems, and over 200 energy-saving stoves have been distributed cutting firewood consumption by 65%.

“These initiatives show that conservation and community development can go hand in hand,” he says. “When people benefit from conservation, they support it.”

The 10 percent fence plan

Building on the success of the elephant exclusion fence, Tsavo Trust introduced the 10 Percent Fence Plan, a smaller-scale solar fence designed for individual farms.

“It’s implemented at the household level. Each family sets aside 10 percent of their land, enclosed with a shorter porcupine fence to prevent crop-raiding wildlife,” Moffat explains. “So far, 19 households within Kamungi Conservancy have adopted this model.”

The plan covers part of the conservancy’s 9,000-acre landscape, reinforcing a “wildlife-friendly zone” where both people and animals coexist peacefully.

From Fear to Coexistence

Riziki, she says. “Now I can sleep peacefully knowing the elephants won’t destroy them. From my home, I can see the fence lines that keep them away.”

Her story, like those of many others in Tsavo, Mtito Andei, Taita Taveta, and the surrounding areas, is proof that innovation, partnership, and community trust can turn conflict into coexistence and fear into hope.