TechLit Digital helping rural school children code their way to brighter future

A four-story building stands out from the rest of the nondescript landscape in Mogotio, a sleepy trade center in Kenya’s Rift Valley region.

Young school children scurry to a room on the top floor.

Software engineer Nelly Cheboi founded the Zawadi Yetu school in 2016 and the TechLit program in 2019.

She oversees around 10,000 students in 30 schools, including one in Uganda. TechLit Africa teaches primary school kids in rural areas digital skills to enable them to find work remotely when they graduate from high school.

According to Cheboi, Zawadi Yetu and TechLit are products of her impoverished childhood.

TechLit school founded to “break cycle of generational poverty”

“I grew up in poverty – sleeping on the floor, not having enough food, and herding cattle instead of playing with friends. My mother sold vegetables by the roadside and struggled to provide for us.

In sixth grade, I started thinking about rewriting my childhood and breaking the generational poverty we were born into. If you are born in a place like Mogotio, you have a 15 percent chance of making it. The odds are not in our favor.”

Cheboi performed well in high school and won a scholarship to study in the U.S. The opportunity was an eye-opener.

“I saw that my childhood was not normal. The things I was struggling with as a kid, which seemed like a luxury, are what every child should have.”

The software engineer’s mind immediately shifted to the children on Mogotio and how she could empower them. The answer came when she discovered technology and computers at age 21 and decided to pursue the course.

“I was horrible- I did not know how to Google and had difficulty typing.”

Cheboi’s lack of basic technological skills compounded her inferiority complex in the United States, having come from rural Kenya.

“I told myself the only reason I was struggling was that I grew up in the village. It was not my fault.”

She recognized the power of technology in transforming societies and started Zawadi Yetu while in her second year of study to teach children digital skills.

“Because I suffered as a kid, they don’t have to. I decided to build a very simple school with a swing set, and it started ballooning from there. I realized it is possible to export this to other schools.”

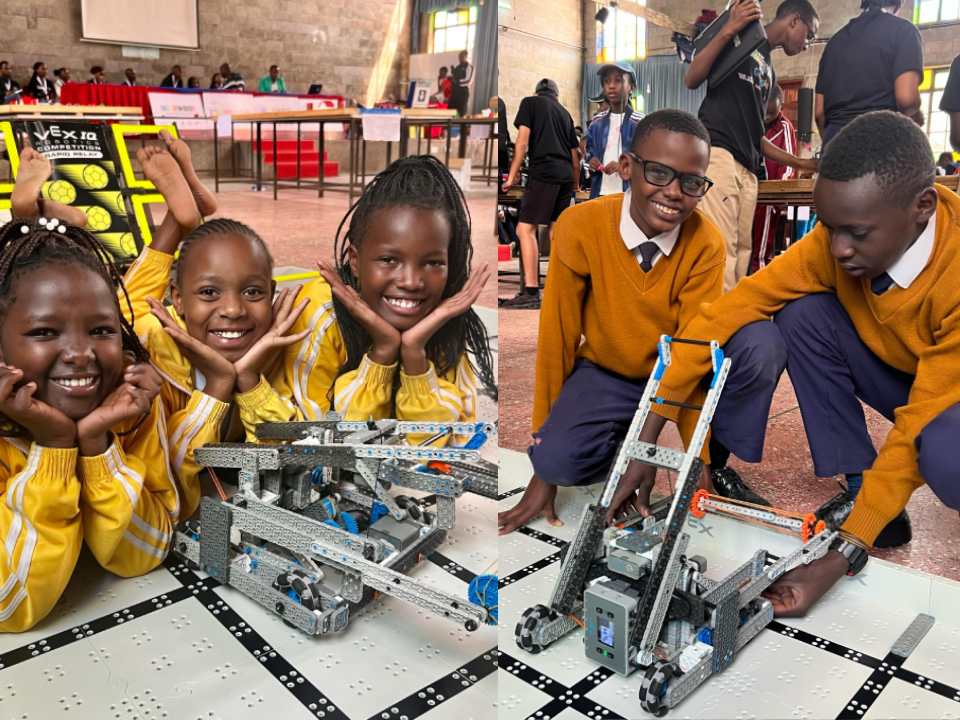

Some of the skills the children learn include robotics, coding in different languages, formatting emails, MoUs, and other documents, designing 2D and 3D images, and creating music.

“They are not just learning how to code, but using technology. It does not matter even if they become farmers, but the aspect of self-efficacy and learning a skill is what we are nurturing.”

Communication and self-efficacy skills are a key part of the curriculum.

“With TechLit, we start backward. We think of when the kids graduate from high school, how they will be able to work? What skills will they need?”

Sustainability at the core of TechLit operations

“We go to any existing school after an invitation by either the institution or a partner. We set up a computer lab run by a TechLit employee. The computers are already installed with our software. We can go anywhere in Kenya and Uganda.”

Cheboi says they charge international partners and NGOs $9,000 a year to run the program in a school, but discount it to $3,000 annually when approached by local schools.

“We have to pay our teachers- they are taxpaying employees with the technological know-how, love children, and with a mindset for growth.”

Sustainability is at the core of TechlLit’s operations, as Cheboi explains:

“These are upcycled computers, 10-15 years old. Most of our computers come from corporations – they discard them after around four years, and to us, that is gold. We ship the computers from Europe and the U.S., refurbish them, and deploy them.

We optimize our software to run on these machines.”

TechLit addresses unemployment

According to the World Bank, nearly 75 percent of Kenyans under 35 face limited job opportunities.

Cheboi sees potential in TechLit changing that narrative for Kenya and the continent.

“Addressing the unemployment figures would require a lot of investment. But what if we tap into an existing market- the digital economy?

What if all the kids had these skills? When they graduate, we are looking at a different country and continent. It would be easy for companies to set up headquarters in Africa because that’s where the skills are.”

Cheboi noted that TechLit faces challenges, including finding partners to fund schools, and employees with the required tech skills.

CGTN Africa editor Regina Mulea contributed to this report.