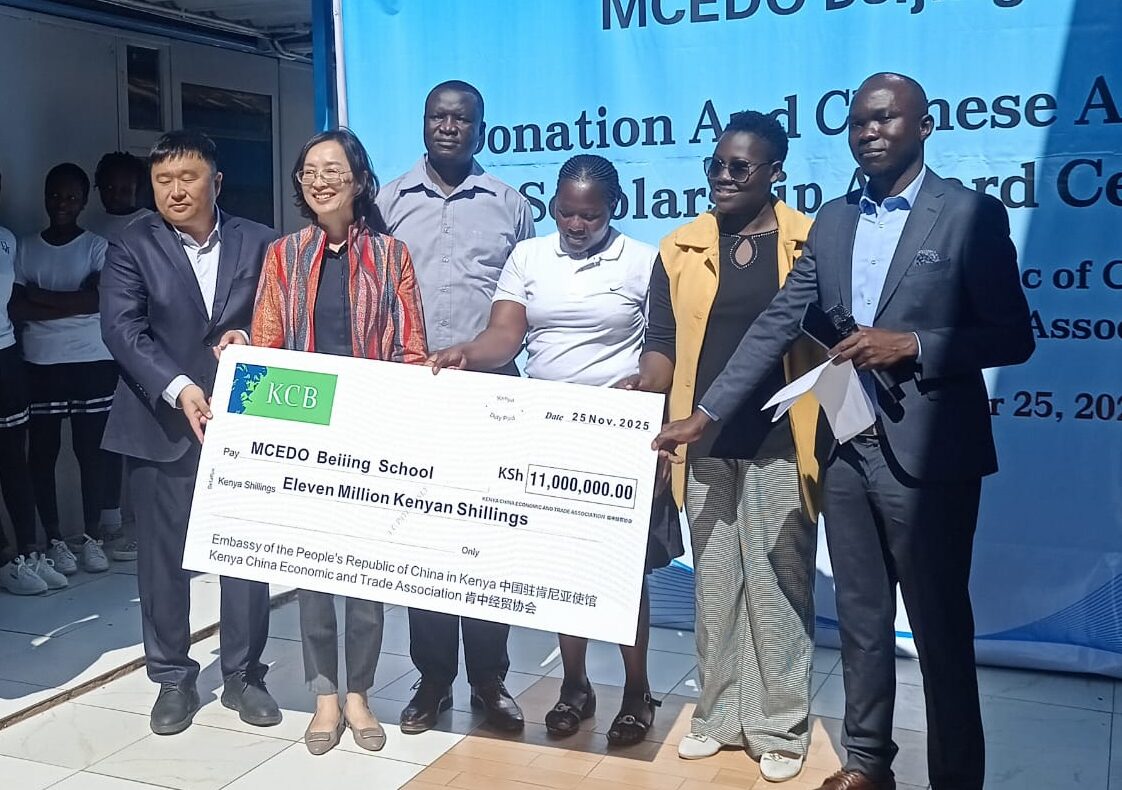

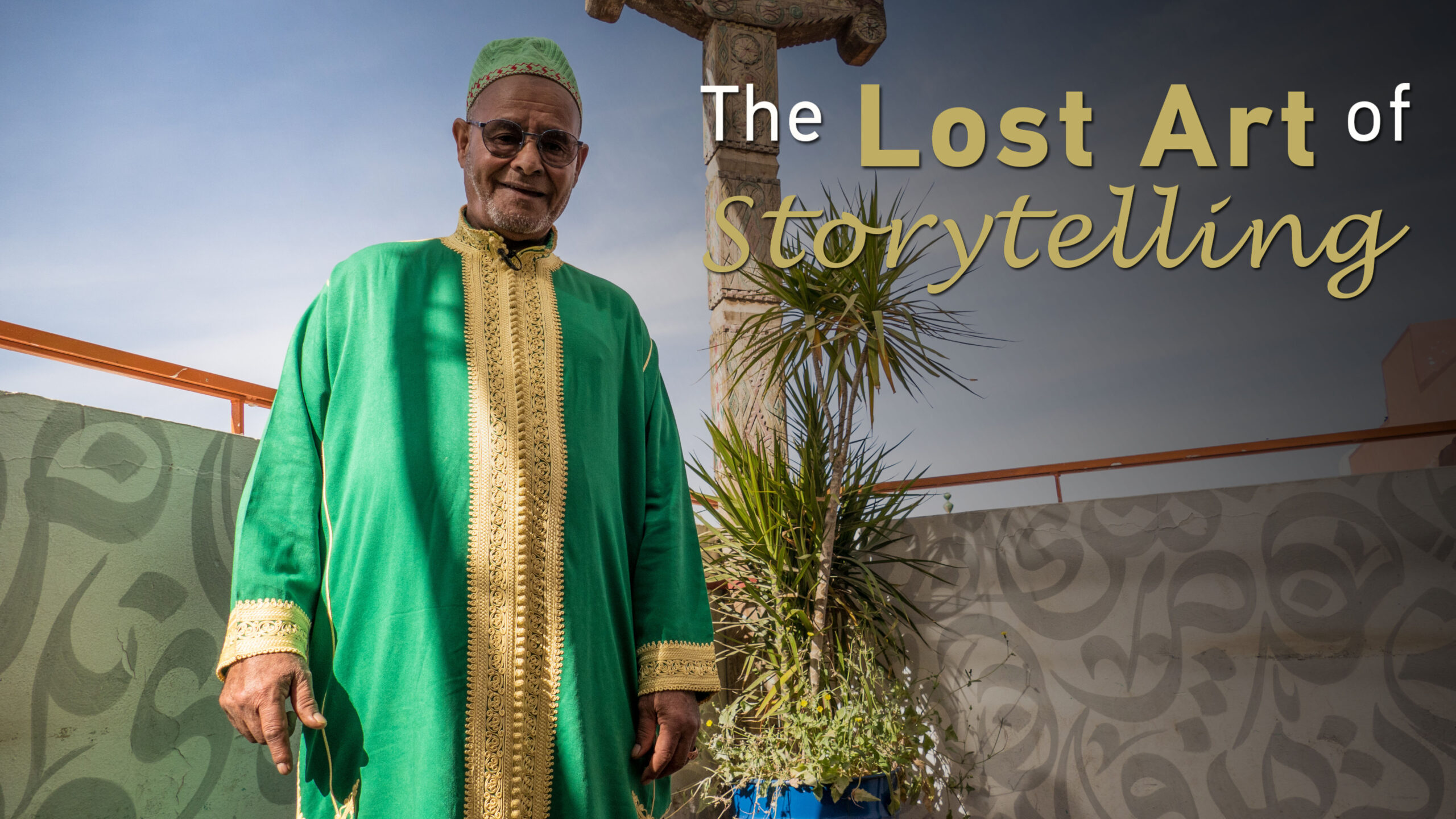

Reporter’s Diary: The Lost Art of Storytelling

They are the voice of Morocco’s medinas. On dry evenings, in crowded streets, they tell, and become, the story of an ancient tradition.

These are Morocco’s last surviving storytellers, or hlaykia as they are otherwise known. Through expressive intonations and gestures practiced from memory, they keep thousand-year-old tales alive.

To the many tourists that cross Jemaa el Fna of Marrakech, these brilliantly dressed narrators are just a fleeting memory – pushed into the bracket with snake charmers and monkey tamers, all part of the seemingly “Morocco experience”.

Little do the tourists know that the hlaykia and their art are on the verge of a silent extinction.

A cafe in the middle of the medina

We were in Cafe Clock, a tight and poetic joint on a narrow street somewhere in Marrakech’s medina. The Clock has garnered a name for itself for its support of Morocco’s art scene. As soon as you entered, you got the feeling that this wasn’t your typical mint tea and pita bread bistro – graffitied walls, multicoloured tables, instruments perched on sofas.

We were waiting for Hajj Ahmed Ezzarghani, a man from Morocco’s mountains who has dedicated most of his life to storytelling.

He’s the man recognised as leading the art’s revival in Morocco.

Originally a travelling salesman – selling coffee at souks – Ahmed would often join the crowds gathering around storytellers. Fascinated by what he heard in the streets, he began to collect Morocco’s traditional fables, and studied the craft until he could tell the stories himself.

Today he is revered as Morocco’s “Master Storyteller”.

“The difference is how you tell them. Every storyteller tells the same story in his own way and style and sometimes even turns it into a song and sings it with his own style,” Ahmed told us.

He was in traditional dress: a green and gold Djellaba, a lime green Taqiyah that was covered by a yellow turban and red slippers.

We spoke to him for over an hour on the past times – the good ol’ days, as he describes them – of Moroccan storytelling. Where they trickled through the ancient trade routes, populated paths beaten by travelling merchants, and found their way to the major cities across North Africa.

“I wanted these stories to come out, to be known. I tell them to people so they memorise them and tell them to others and so forth. It’s better to learn them by heart, memorise them, this way they will never disappear or die.”

Ahmed noticed a change in the youth. Fewer people were interested in the more traditional forms of storytelling, instead, turning to modern ways of teaching, socialising and playing. What was left – ageing storytellers making their way in the market-jungle of Morocco’s major medinas.

Like the old saying in Marrakech, “when a storyteller dies, a library burns”, when they die there are few who can carry on the trade. Most stories are in the heads of those tellers, they take their repertoire to the grave.

Teaching a new generation

But Ahmed decided to fight for his trade on a new front. Using the subtle setting of Cafe Clock, he laid out the framework to pass the tradition onto the new generation.

“The stories we care about the most are the ones our grandmothers used to tell their kids when they used to put them to bed,” Ahmed told me.

“We don’t want these stories to disappear. That’s why I wanted to work with students to teach them this patrimony and culture and those students are clever, they memorise these stories and treasure them.

“These are the things we were afraid to lose because they are not registered or written anywhere.”

Once a week, Ahmed teaches a small group of aspiring storytellers on the fundamentals of the art. Although the group is modest in size, he has managed to persuade his students to spread the word of storytelling.

“We come to learn stories from Ahmed and this is in order to keep them alive, to keep the Moroccan storytelling tradition going, if not – it will fade” one female student told me.

“We young people must do this, most storytellers are either sick, or too old and they hardly perform anymore.”

Ahmed is determined not to lose the art he has dedicated his life to. Facing significant hurdles in an ever-changing world, he is one of the only people alive who can save Morocco’s storytellers.

“All we care about and left to us are the stories about culture and patrimony. We didn’t know how and where to register these stories and keep them, so our only way is through those young people.”