Kenya doctor launches crusade against cleft lip and palate

It is estimated that worldwide, every three minutes a child is born with a cleft. That works out roughly to one in 500-750 births. In Kenya, the odds are one in every 500 births.

Sometimes a cleft condition can be easy to detect because the birth defect affects the lip. In other cases, it’s harder to detect when someone has a cleft because the opening is in the roof of the mouth or palate, hence the term, cleft palate.

To find what exactly causes cleft lip and palate we spoke to Dr. Meshack Onguti, a reconstructive surgeon in Nairobi.

Dr. Onguti says there is no specific scientific cause, however, there are many risk factors which increase the likelihood of the birth defect. Genetics and family history, pre-existing medical conditions, poor nutrition and exposure to harmful environmental substances can affect the healthy development of a baby. As a result, these factors could also help contribute to the development of a cleft.

“Genetics, genes themselves whereby the disease or the problem could be carried on in the families,” says Dr. Onguti. “The other thing they’ve found out is that mothers who heavily smoke and take alcohol…when you do that, the alcohol and smoking deprives a lot of nutrition from the body. And they’ve found they have a higher incidence of having children with a cleft lip and palate in those cases”.

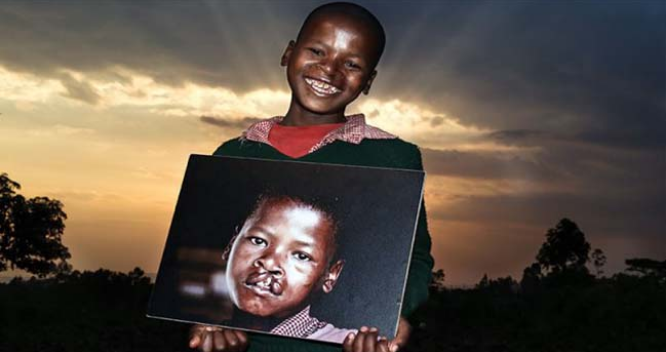

Once a cleft is discovered, doctors advise that treatment begin immediately. Not only will treatment restore a normal look but it will improve important functions such as the ability to eat and drink, and in the case of infants, the ability to suckle well. Proper treatment of cleft lip and palate also increases the chances of learning to speak properly as children grow older.

But getting proper treatment is challenging, particularly in poorer countries.

“As you can imagine, not many professionals offer this treatment, particularly in the reserve areas, that’s why we do at least monthly free medical drives to be able to reach the interior population”, says Dr. Onguti.

Even in populated urban areas, the cost is often far out of reach for most people.

Lucia Muoki knows firsthand about the financial costs of clefts. She now works with Dr. Ogunti to help people like her find treatment.

“What I am spending is close to Kenyan shillings 200,000-250,000 ($2000-2500) that is for the dental, for the cleft palate treatment,” Muoki says. When we look at most private hospitals they charge around Kenyan Shillings 250,000,300,000 ($2500-3000). Then if we add also the cleft lip the whole package, the cost is maybe 600,000 Kenyan shillings ($6000).

The social stigma of cleft lip and palate often also serves as an impediment to getting treatment.

“In some communities they hid their children, claiming the kid has juju (witchcraft) but that’s very unfortunate.” Dr. Ogunti says. In certain countries isn’t common for parents of children born with the defect to hide or abandon their children, or worse. A 2017 study produced by the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association documented cleft-related infanticide in 27 countries, with most of the reports coming from China, India, Nigeria, Russia, and Peru.

Muoki says having a cleft greatly affected her self–esteem.

“Basically growing up with a cleft palate and lip with this defect wasn’t much of an issue for me because from 0-12 nothing really registers we are kids you know; and we just brush it off but when I got to the age of realization around 14-15 years when I become a teenager and that’s when I looked at myself and asked, hey what’s happening, I don’t look like any other kids”.

To help encourage people to get treatment, organizations such as Dr. Ogunti’s “Help a Child Face Tomorrow” attack myths and misconceptions associated with cleft lip and palate. One of his biggest challenges is convincing insurance companies to cover the treatment.

“This is not a beauty procedure, because the cleft lip and palate affects the normal functioning of the mouth and I always tell the insurances, look don’t consider this as a cosmetic thing this is a problem that affects function it will affect, eating speech the parents so many things.”

Dr. Ogunti also wants the government they should consider cleft lip and palate as a disability. The designation would allow people born with the defect to qualify for NHIF to get universal coverage.