From hashtags to injections: Ozempic’s role in Kenya’s weight loss craze

At first, it looked like just another trend sweeping Kenya’s restless social media scene. Celebrities and influencers posting slimmer silhouettes, pairing before-and-after collages with candid confessions about a once little-known drug: Ozempic.

Influencers lead the charge

Lydia Wanjiru, a lifestyle content creator with a devoted following, is among the most outspoken. In one video on her YouTube channel, she described how the injections helped her shed over 10 kilograms in a matter of months.

“When I started Ozempic…I was exactly 100 kgs. As of last week on Tuesday…I was 84 kgs. So, meaning I’ve lost 16 kgs after three pens of Ozempic,” Wanjiru said. “Seeing myself below 80 kgs was such a moment for me…the least I’ve ever seen myself is 95kgs.”

Sandra Dacha, Pritty Vishy, and Kelvin Kinuthia are a few of the other Kenyan influencers proudly touting Ozempic in their weight loss journeys. They openly speak about it on their social media platforms, sharing where they get the shots.

Ozempic helps with weight loss by mimicking a natural hormone called GLP-1, which regulates appetite and blood sugar. It slows down digestion, making you feel full longer, while also sending signals to the brain that reduce hunger and food cravings. At the same time, it helps control blood sugar by boosting insulin release and lowering glucagon. Together, these effects lead people to eat less and gradually lose weight. The weight often returns if the medication is stopped without lifestyle changes.

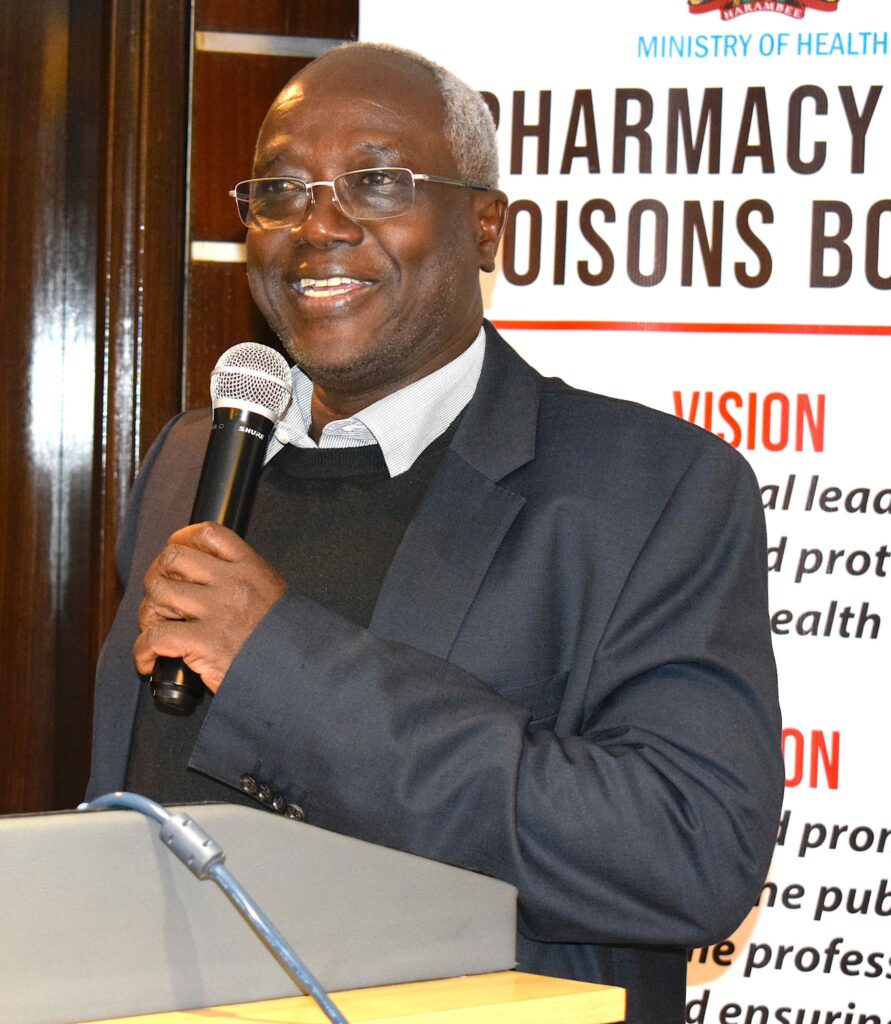

Regulators sound the alarm

But the excitement has been met with a wave of concern. On August 19, Kenya’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board, the country’s top drug regulator, issued a statement warning against the misuse of semaglutide, the compound sold under the brand name Ozempic. The board stressed that while the drug is approved in the country for treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus, it remains a prescription-only medication and should not be administered outside its approved medical purpose. Misuse, it said, can lead to severe complications, including intestinal obstruction, acid reflux disease, hypoglycemia, and eye conditions.

Doctors echo those fears.

“Semaglutide can cause nausea, headache, bloating, gastritis, constipation, and diarrhea,” said Dr. Caroline Mithi, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist in Nairobi. “It can also cause severe side effects, including acute pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and thyroid cancer if you have a family history of medullary thyroid cancer.”

A global phenomenon meets local pressures

Kenya is hardly alone in its fascination. Across the world, semaglutide has been celebrated as a miracle drug, its promise of effortless weight loss upending the diet industry. But in Nairobi, the phenomenon collides with a rapidly expanding influencer economy, where body image is both content and currency. Posts documenting weekly injections rack up hundreds of thousands of views, often overshadowing the cautionary notes buried in the captions.

The risk of overshadowing diabetes care

The off-label demand, some physicians fear, could eventually overshadow Ozempic’s original purpose: treating diabetes. With its popularity rising, patients who rely on Ozempic for blood-sugar control risk facing shortages or inflated costs.

One Nairobi-based clinic, frequently mentioned by social media influencers, has quietly operated for the past three years. When it first opened, the clinic charged $1,547 for each Ozempic pen. It now charges $580.

According to an administrator who identified herself as “Miriam”, clients there have been using Ozempic pens for over a year, shedding between five and 10 kilograms each month. She insisted that patients are briefed on both short- and long-term side effects beforehand, since every treatment begins with a consultation.

However, when asked to speak directly with the doctor in charge, “Miriam” said potential patients would first need to pay roughly $270 for “consultation” purposes. When pressed further, requesting the doctor’s email, she replied flatly: “She doesn’t respond to emails.”

A call for safeguards

For now, Kenya’s regulators are urging restraint, while doctors press for stricter safeguards.

“Semaglutide should be a prescription-only medication, prescribed in a medical facility, and prescribed after evaluation of labs and assessment of possible risks that may be encountered.” Dr. Mithi said.

As Ozempic’s use in Kenya grows, the nation finds itself at a crossroads, caught between the promises of modern medicine and the pressures of a culture that prizes rapid transformation.