Cleophas Mandela: The sculptor who breathes life into Kenya’s icons

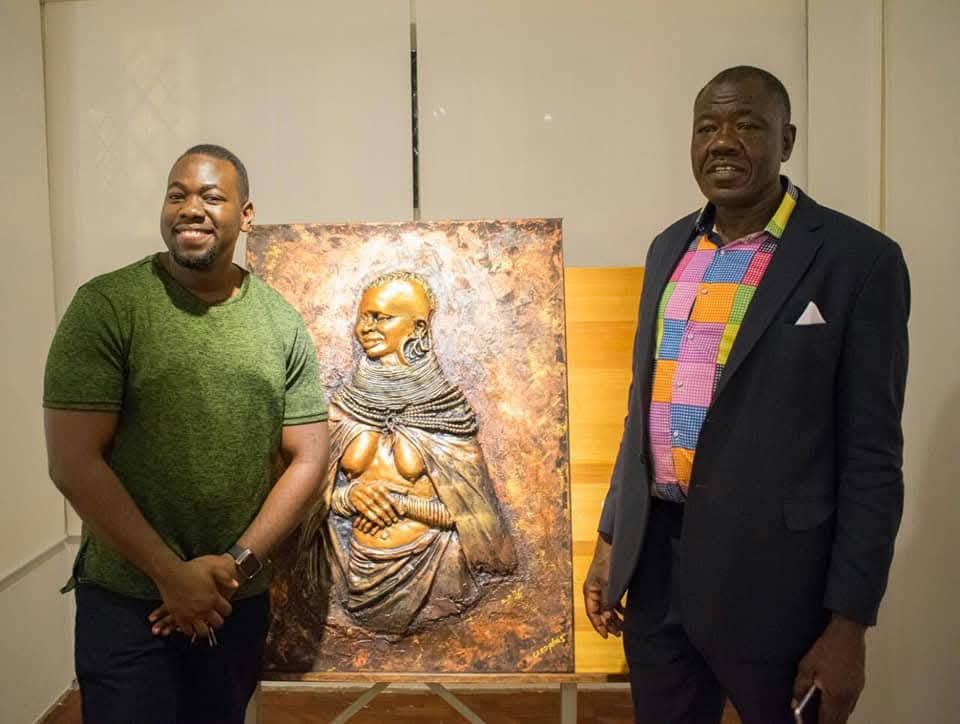

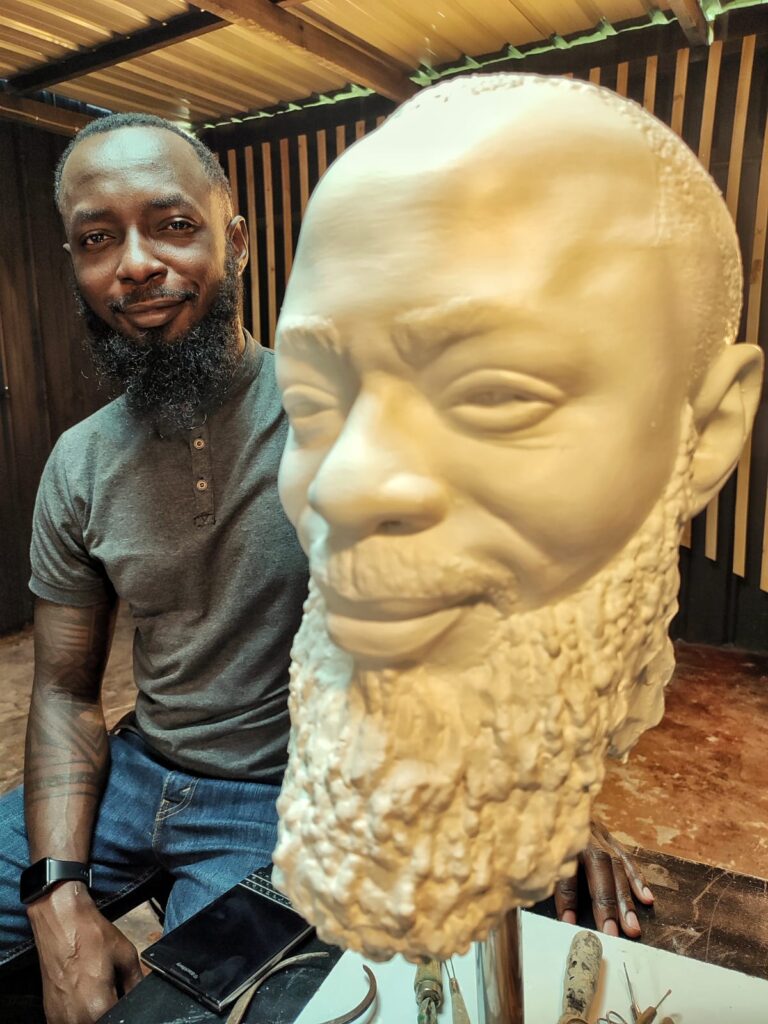

A replica of the bust that first brought him widespread recognition is of Eliud Kipchoge, captured in his iconic stance — arms akimbo, standing beside the artist behind the work. The piece, instantly recognizable and deeply symbolic, carries the unmistakable touch of Cleophas Mandela’s hands, blending athletic triumph with artistic mastery. It is through such works that Mandela carved his place in Kenya’s contemporary art scene, translating moments of national pride into lasting monuments.

Honoring History Through Art

When Cleophas Mandela speaks about his craft, it is clear that sculpting is not just a career for him — it is a calling, a way of honoring memory and history through art. His works are not simply statues; they are reminders of Kenya’s heroes, stories, and eras, frozen in bronze, fiberglass, or stone.

“With Daniel Arap Moi, I tried to capture the hues of his red tie, his signature rose, and his ivory staff,” Mandela says with quiet pride. The lifesize sculpture of Kenya’s second president took him eight months to complete, a painstaking process that demanded patience, precision, and an eye for detail.

Mandela’s journey into art began at the age of 15. It was not by chance. He inherited the craft from his late father, Luke Oshoto Ondula, a legendary sculptor and artist whose works earned international acclaim. Growing up, Mandela would often watch his father at work, surrounded by chisels, clay, and bronze casts, absorbing techniques long before he ever tried them himself. Ondula’s reputation stretched far beyond Kenya’s borders. His artistry is immortalized in the Royal Queen’s collection in London and a prestigious commission in Dar es Salaam for Tanzania’s founding father, Julius Nyerere. He also created a painting for former Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, showcasing his ability to adapt across media.

Like Father, Like Son

“I used to admire watching my father create his art,” Mandela recalls. “I was very present in every stage he undertook, from sketching and molding to the final piece. I wanted to tap into his skills because he had already made a name for himself through his work, and I hoped he would pass those skills on to me.”

Within Kenya, Ondula’s works are landmarks in their own right: the towering Tom Mboya statue in Nairobi’s bustling CBD, a daily reminder of a political giant; the Naked Boy sculpture at the High Court, a bold piece that continues to spark curiosity and reflection; and the stately lion sculptures at the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga mausoleum, symbols of strength and legacy. These pieces not only cemented Ondula’s place in African art history but also laid a strong foundation for Mandela, who grew up inspired by both the grandeur of the works and the respect his father commanded as an artist. For Mandela, carrying forward this legacy was less about obligation and more about destiny, a natural continuation of a story written long before him

Carrying that torch, Mandela carved his own path. His first attempt was a relief piece of a flamingo against the scenic landscape of Naivasha. His portfolio now includes sculptures of celebrated figures such as Edi Gathegi, Lupita Nyong’o, and Daniel Arap Moi. Most of his life-size works take approximately four months to complete, while larger-than-life commissions may require six to eight months.

“The best part of this work is doing the finer details, the facial expressions, the eyes, the wrinkles. All these give me a deeper connection,” he says.

A Process Rooted in Patience and Precision

Mandela’s process blends creativity with discipline. He begins with reference images and preliminary sketches before moving to a maquette — a miniature model that guides the final work. For modeling, he uses plasticine, valued for its malleability and resistance to drying out. For casting, he turns to bonded bronze, a blend of epoxy resin and bronze filings that ensures durability, especially for outdoor pieces.

Every commission begins with a conversation.

“We always consult with the client — is the piece going indoors or outdoors? That determines which materials we use. Fiberglass works well for indoor pieces, while bonded bronze is best for outdoors,” he explains. Once complete, Mandela and his partner, Cheryl Nagawa, create digital placement images to help clients visualize how the artwork will look in its final location.

Inspiration From Kenya and Its People

What sets Mandela apart is not just his technique but his source of inspiration.

“I draw inspiration from the Kenyan people and our different ethnicities,” he says. “I get to see and appreciate the different facial and body features everyone has. Every face tells a story. Whether it’s a smile line, the shape of the nose, or the way someone carries themselves, these details help me bring out personality and spirit in my sculptures.”

Still, he admits the process is not always smooth.

“Most of the sculptures surprise me. There’s always that stage where you feel it won’t come out the way you envisioned. The clay seems stubborn, the proportions don’t align, or the expression feels flat. But then, with patience and persistence, something shifts. The piece slowly begins to take life, and most of the time, I end up surprising myself.”

For Mandela, these moments of doubt and breakthrough are what make sculpting meaningful. They remind him that art is not just about skill but about trust in the process — allowing the work to evolve naturally until it finds its own form.

Between Tradition and Technology

The rise of 3D printing and CNC machining poses both opportunities and challenges to sculptors like Mandela. While these technologies promise speed, precision, and the ability to replicate works at scale, he believes the essence of sculpture lies in the human touch.

“Yes, 3D printing and CNC will probably take some of our work, but not immediately. Most people still appreciate works done by hand,” he says.

For Mandela, the difference is not just in the outcome but in the journey. Machines can reproduce form, but they cannot capture the subtle decisions, instinctive corrections, and emotional connection that an artist weaves into a piece.

“When you work with your hands, you leave a part of yourself in the art, your mood, your patience, even the mistakes that turn into character. That’s something no machine can replicate. People naturally connect more with sculptures crafted by hand,” he explains.

Still, Mandela does not dismiss technology outright. He sees potential for collaboration, where 3D tools can assist with preliminary models or large-scale projects, allowing artists to save time and focus on the intricate details that truly define their craft.

“Technology can support us, but it should not erase us. At the end of the day, art is about soul, and soul cannot be printed.”

Building a Legacy

Much of Mandela’s work comes through referrals, many of them linked to his father’s long-standing clientele. But times are changing.

“Through social media, we are also reaching new clients,” Nagawa adds, noting how digital platforms have reshaped access to art and broadened their reach beyond traditional networks. Platforms like Instagram and Facebook now act as virtual galleries, allowing Mandela to showcase his process and finished works to audiences he might never meet in person.

He is an artist whose versatility sets him apart. Mandela creates grand monuments and public statues that command attention in cityscapes, yet he also pours the same dedication into portraits, reliefs, and individual pieces for private collections. This range demonstrates not only his technical mastery but also his ability to adapt his craft to different contexts — from honoring national heroes with life-size bronze figures to crafting intimate works that capture personal stories and emotions.

“Now I have pieces that will help me establish a gallery, which is what I’m currently working on. Most of the time when I create a piece for a client, I also duplicate one for record and marking purposes.”

For Mandela, each project is unique, but the goal is the same: to preserve memory and evoke meaning. Whether it’s a public monument that speaks to a nation’s collective history or a small commissioned sculpture that holds personal significance for a family, his artistry bridges both the monumental and the intimate.

A Journey of Heritage and Hope

For Mandela, sculpting is more than chisels, clay, or bronze. It is about memory, heritage, and storytelling. Each piece — whether a towering life-size figure or a small relief artwork — carries with it the weight of history and the pride of Kenyan identity. His hands do not just shape form; they preserve voices, moments, and legacies that might otherwise fade with time.

And as partner Nagawa observes in reflecting on his work, Mandela’s sculptures are not just artistic creations, but emotional touchstones. They stir remembrance, spark conversations, and remind Kenyans of where they have come from.

“If I sculpt a piece of Moi, I want you to start reminiscing about the Moi era,” Mandela says. It is this ability to blend artistry with memory that makes his work timeless.

From a 15-year-old boy sketching flamingos to a sculptor shaping the legacies of Kenya’s most iconic figures, Cleophas Mandela is proving that art can outlive its maker. His dream is not only to honor Kenya’s heroes but also to inspire future generations, one sculpture at a time.

Already, he is working toward establishing his own gallery, a space where history, culture, and creativity will converge to nurture future artists and storytellers.