China makes history as Chang’e 4 probe lands on far side of the moon

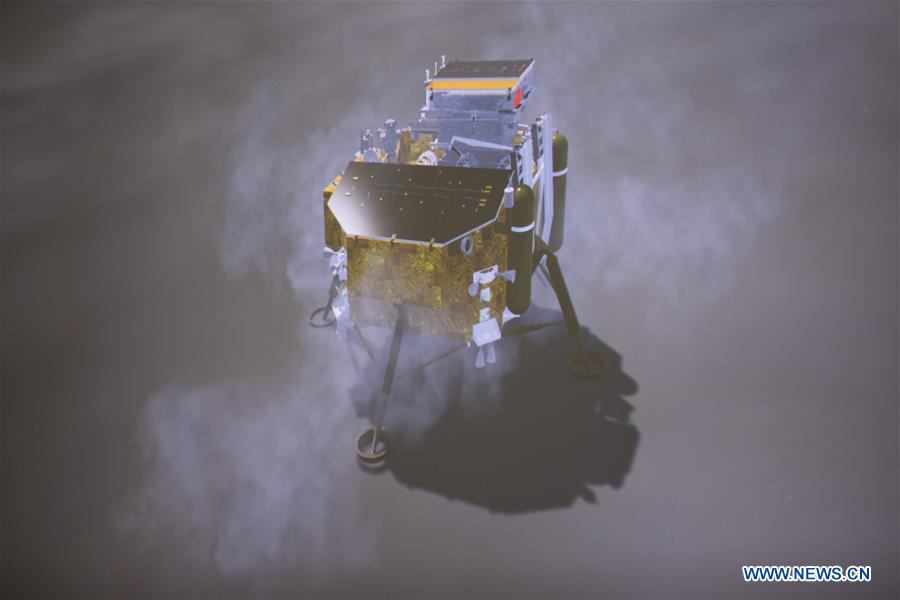

China’s Chang’e-4 probe touched down on the far side of the moon Thursday, becoming the first spacecraft soft-landing on the moon’s uncharted side never visible from Earth.

Citing the China National Space Administration, Xinhua said the space probe, made up of a lander and a rover, “landed at the preselected landing area on the far side of the moon at 10:26 a.m. Beijing Time.”

Landing on the far side is a technical challenge, as there is no direct way to communicate with the spacecraft as it nears its target. China put a relay satellite in orbit around the moon in May to overcome that communication challenge.

Courtesy: Xinhua

The far side of the moon has been seen and mapped before, even by astronauts of the Apollo missions. But the successful landing of Chang’e 4 represents the first time any spacecraft has touched down on the moon’s far side.

Over about 12 dramatic minutes, China’s Chang’e-4 probe descended and softly touched down on a crater on the far side of the moon on Thursday.

Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar exploration program, said Chang’e-3 landed on the Sinus Iridum, or the Bay of Rainbows, on the moon’s near side, which is as flat as the north China plain, while the landing site of Chang’e-4 is as rugged as the high mountains and lofty hills of southwest China’s Sichuan Province.

Courtesy: Xinhua

Chinese space experts chose the Von Karman Crater in the South Pole-Aitken Basin as the landing site of Chang’e-4. The area available for the landing is only one-eighth of that for Chang’e-3, and is surrounded by mountains as high as 10 km.

Unlike the parabolic curve of Chang’e-3’s descent trajectory, Chang’e-4 made an almost vertical landing, said Wu.

“It was a great challenge with the short time, high difficulty and risks,” Wu said.

The whole process was automatic with no intervention from ground control, but the relay satellite transmitted images of the landing process back to Earth, he said.

“We chose a vertical descent strategy to avoid the influence of the mountains on the flight track,” said Zhang He, executive director of the Chang’e-4 probe project, from the China Academy of Space Technology.

Li Fei, one of the designers of the lander, said when the process began, an engine was ignited to lower the craft’s relative velocity from 1.7 km per second to close to zero, and the probe’s attitude was adjusted to face the moon and descend vertically.

When it descended to an altitude of about 2 km, its cameras took pictures of the lunar surface so the probe could identify large obstacles such as rocks or craters, said Wu Xueying, deputy chief designer of the Chang’e-4 probe.

At 100 meters above the surface, it hovered to identify smaller obstacles and measure the slopes on the lunar surface, Wu said.

After calculation, the probe found the safest site and continued its descent. When it was 2 meters above the surface, the engine stopped, and the spacecraft landed with four legs cushioning against the shock.