Africa rises to combat drought and desertification

The African Union estimates that 485 million people on the continent are directly affected by land degradation. Furthermore, droughts account for more than 44 percent of all global drought-related disasters.

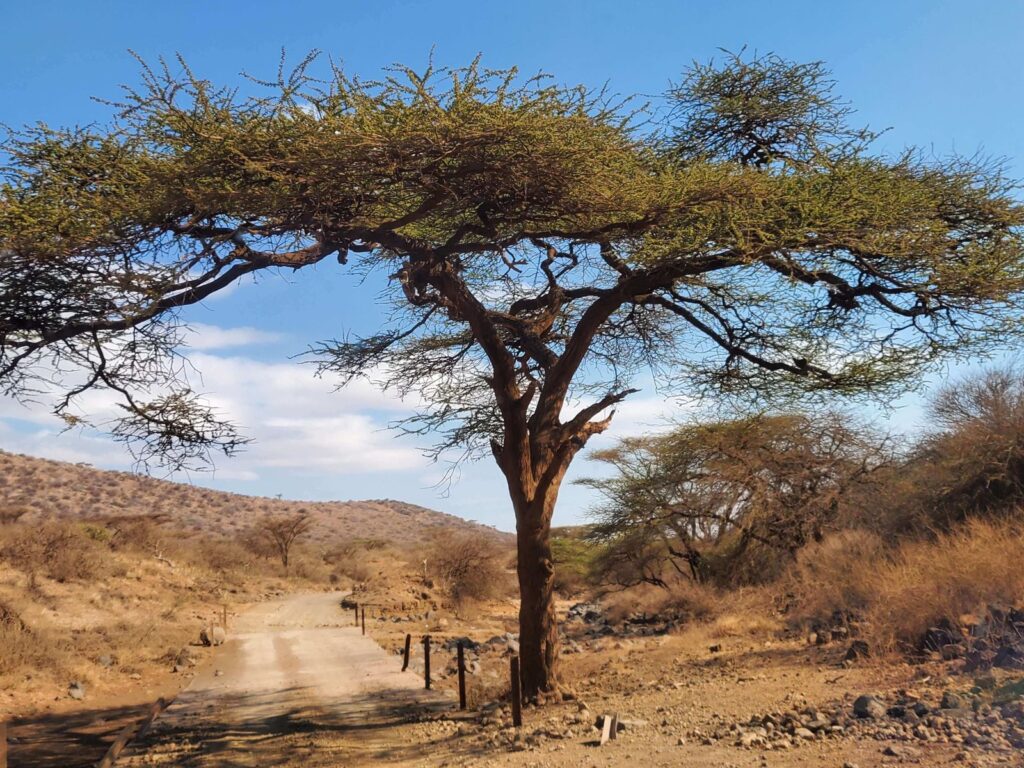

In regions like the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, drought cycles are wilting crops, wiping out agricultural yields and reducing livestock populations.

“Drought is pertinent to the whole continent,” explains Dr. Tahira Shariff Mohamed from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and The Jameel Observatory for Food Security Early Action. “But in particular, the drylands are the most affected areas because of their ecological predisposition, often receiving minimal and variable rain compared to the highland areas and because of this pattern, it is prone to drought condition.”

Contributing factors

Dr. Mohamed says that while climate change remains the primary driver of droughts, a critical gap remains in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

“The number one factor is the climatic condition which I had mentioned earlier because of variability in rainfall patterns. Other than the climatic factor, what makes the condition difficult is a lack of proper planning and the long-term structural marginalization of the drylands,” she explains.

Despite having “very robust early warning systems that ensures that we know whether the rain will come in the next three months or not,” she notes that the real challenge lies in inadequate planning and resource allocation.

“If we don’t plan in advance in terms of how we can respond when there is a drought and we don’t have the resources such as finances to anticipate and act ahead of the disaster, then, the chances of failing to achieve a drought disaster resilient continent is high”.

Additional factors contributing to the crisis include overgrazing and unsustainable farming practices, deforestation and loss of vegetation cover and poor water and infrastructure management. Unfortunately, this is often promoted by development projects that promote sedentary and despise mobility, an essential practice of utilising parchy dryland resources.

Drought Management: Hope on the horizon

Mohamed points to preparedness as the best solution for drought management through innovations such as Anticipatory Early Action, a tool developed mainly by humanitarian agencies anchored on pre-agreed action and pre-financed intervention, often triggered by early warning information with the aim of reducing the effect of disasters.

“This means that when we have reliable early warning information and we know it is going to affect certain populations in certain areas then we try to improve the water infrastructure so that animals will have access to water. We invest in feed so that animals will have enough fodder for the dry season and we also invest in health services so that the diseases that accompany drought is treated in advance.”

She also highlights Index-Based Livestock Insurance, which her organisation leads. “They assess the vegetation condition and if the vegetation is below a certain threshold, then they give a payout to the insurance beneficiaries,” she explains.

Amidst the scientific and structural advancements, there’s also a growing recognition of the invaluable role of traditional knowledge in drought resilience.

One powerful example of traditional drought-fighting knowledge is the use of zaï pits in Burkina Faso, also known as Chololo pits (Tanzania) or agun pits (Sudan). The farming technique involves farmers digging small holes where the seeds of crops are planted, and then filling them with organic matter such as compost or manure.

When rain arrives, these pits capture water and nutrients.

According to Greener Land, an organisation focused on spreading awareness about landscape degradation, zai pits can be beneficial for soil conditions and are a very successful method to allow for the growth of vegetation in dry areas.

“One thing I know for sure and even scientists who have worked in areas affected by drought know that traditional knowledge is a resource that people have relied on for centuries,” she said. “They know when a drought is coming, they know where to move their animals, how to move but many times this knowledge is seen as secondary knowledge and is not taken seriously.”

African governments and regional bodies have also joined the fight in efforts to tackle this crisis.

Initiatives such as the Great Green Wall and the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) are a collaboration between many African countries hoping to restore hectares of currently degraded land and create jobs on the continent.

Dr. Mohamed concludes by calling for a more collaborative approach to solving this crisis. “What we need is goodwill from the government, embedding the anticipatory action planning for drought management and also financing because if you don’t finance then the early warnings will not be useful.”

Report by Regina Mulea