Coastal Kenyan methadone program struggles to be effective

When the Omari Project was founded in 1995, only one drug user had died due to addiction-related complications. Since then, drug use and addiction have worsened in the region, leading to many more deaths.

Malindi becomes key drug transport point

Omari exists because of Malindi’s increasing popularity as a transit point for the trans-Indian Ocean drug trade that moves products from South Asia to South Africa and the Americas. At the same time, a local drug-using community has become more visible throughout the years and now constitutes a threat to the local community, according to Athmani Lali Omar, who authored A Small Town Drug Problem: The Socio-Economy of Malindi’s Heroin-Using Population for the SIT Graduate Institute.

The project is named for a drug user who died when all his veins collapsed.

“Naming the facility after him was to serve as a frightening reminder of the dangerous consequences of using heroin,” founder Harrison Alias Bakari Mwambogo says. The shock of this death led Mwambogo and others to set up the Omari Project. They later secured government funding to help other addicts avoid a similar fate.

Addicts, commonly referred to as Mateja, loiter through the town. Many hang out in dens sequestered in construction sites or along the beach, often posing a security threat.

Kenya’s National Police Service’s official statistics show a 60 percent increase in illegal drug arrests from 1997 to 2004. Omar’s study approximates that the number may have been about 1,000 in 2005. Presently, there are no conclusive stats on the exact number.

Heroin addiction spreads

In a recent survey from an anti-drug campaign by Kenya’s National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA), heroin abuse is a critical problem in the coastal region. Its data shows that 1 in 6 Kenyans aged 15-65 struggle with drug abuse. Furthermore, NACADA statistics put drug abuse prevalence at 10.5 percent of the entire coastal population, with heroin abuse in the lead.

However, as heroin addiction spread in Malindi in Kilifi County and its environs, the Omari project team lobbied for the introduction of drug-assisted therapy for those looking to get clean.

“The problem kept getting worse, with some sharing syringes and infecting each other with all manner of diseases and others having transactional sex for money to buy drugs. This, also motivated us to lobby for methadone, and in 2015, we inducted the first client,” Mwambogo said.

Methadone is a key drug used in the treatment and management of opioid dependence. Listed on the World Health Organization (WHO) essential drugs list, it plays a crucial role in opioid agonist maintenance therapy and withdrawal management. Simply put, the drug helps people addicted to opioids, like heroin, safely manage their cravings and reduce the withdrawal effects, giving them a chance to recover from addiction.

MAT Clinic tries methadone treatment

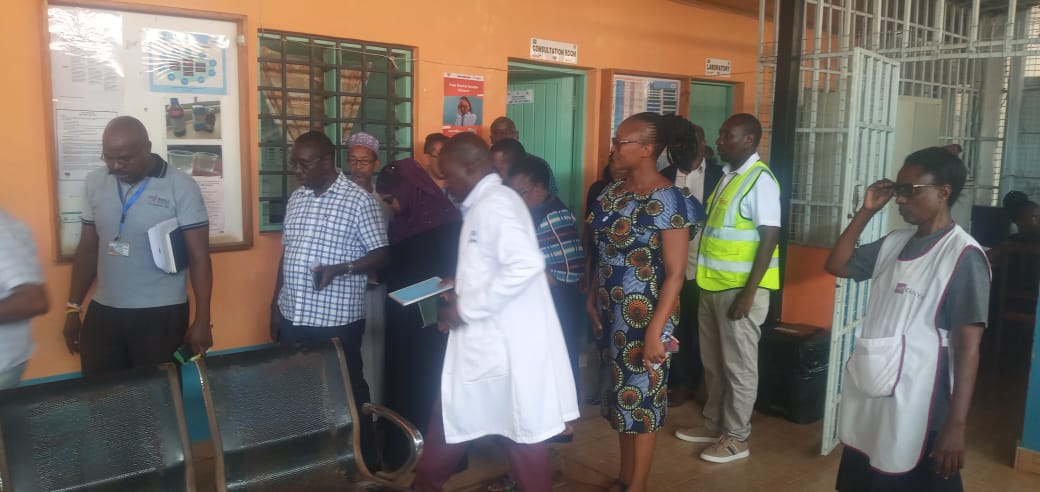

Every weekday, at a medically assisted therapy (MAT) clinic, former addicts queue for a dose intended to keep them off heroin. Between 9 a.m. and noon, patients receive the drug orally through a small window overlooking the outpatient area.

The MAT clinic provides targeted treatment to individuals addicted to heroin. According to Dr. Kelvin Mboa, methadone is ideal for heroin users because of its ability to significantly reduce cravings and alleviate the harsh withdrawal symptoms that often come with attempting to quit heroin.

“We identify the user from their dens, give them motivational talks, then get them into therapy where they can get treatment for other medical conditions they may have, such as Hepatitis C, TB, and HIV,” Dr Mbowa said.

The program has treated 1,360 people since its inception in 2015. Out of these, it has only discharged 200.

“Only 20 percent of those enrolled in the program have been discharged, having completed the therapy and having shown desirable outcomes that will warrant us to let them go on with their lives in the community,” Dr. Mbowa said.

Dr Mbowa equates the use of methadone to using a seat belt in a vehicle, as it only reduces the chances of one getting hurt, but ultimately doesn’t eliminate the possibility of an accident.

“While the craving among users is significantly reduced, there is still a supply of the drug outside. We know this because, as we tend to the older cohort of recovering addicts, we receive a fresh cohort of much younger users. That tells you that there is still a healthy supply of addictive substances right outside the hospital,” he said.

“We are recycling addicts”

Users lose social standing, economic worth, and psychological health. This means while using methadone eliminates cravings, they require other forms of support like counseling and a reintegration program, according to Dr. Kelvin Mbowa.

“This model works as an outpatient; we can’t control their activities outside the facility,” says Dr. Mbowa, implying that the syrup alone is not enough in a society brimming with temptation, especially for patients with no support system.

Mwambogo explains that it boils down to finding a suitable inpatient rehab facility that will take the reins after one starts the program.

“An exit plan, which would be an aftercare program, lacks in this area. After taking methadone, then what? If this individual has nothing to do, they will go back to the drug dens. We are just recycling them,” he said.

He says they need jobs or vocational training to secure a fresh start in life, otherwise, it remains a cyclical zero-sum game where one is initiated, gets addicted, enrolls in methadone therapy, and then heads back to the only life they know, this time as a peddler.

Some addicts turn to crime

Unfortunately for the Malindi methadone program, the absence of an aftercare program has borne a new crop of addicts that are now engaged in criminal behavior, attacking locals and engaging in robbery so they can sustain their new habit, says a former addict and coordinator for the program.

The former addict, who wishes to remain anonymous, says that what makes methadone ineffective or perceived as unsuccessful in Malindi is the excessive drug use and peddling in the streets. Once a person leaves the clinic after taking methadone, triggers are everywhere.

“The recovering addict will want to try out these other drugs, once this happens, he or she gets used to this mix. This is what is making the methadone approach unsuccessful here. You will find that one will take methadone, then go out and also take khat, skunk, marijuana… Methadone is not a great success because, ideally, these guys need to have been given jobs. When left idle, they try out other readily available drugs,” he says.